How can long-distance cross-border passenger rail services in Europe be promoted in a better way?

The EU, Germany and many other European countries have communicated ambitious growth targets for rail passenger transport. In a study, which was initiated by the European Commission (EUC), civity analysed multiple options focussing on track access charges, which could potentially support these train services and foster growth beyond their historically low share of 6–7% of total passenger kilometres in European rail.

In cooperation with the European Infrastructure Managers, civity found out that new charging approaches can be considered for promoting long-distance cross-border passenger services, some of which are already in practical use today. However, the promotion of international rail services based on track access charges (TAC) reaches its limits where balanced financing of the rail infrastructure is endangered.

TAC are currently neither designed nor intended as a promotional instrument to foster long-distance cross-border passenger services. Rather, they are an element of user financing, aiming to contribute to the cost recovery of the infrastructure managers (IM). This charging approach is guided by the economic principle that user charges based on marginal costs ensure the optimal usage of infrastructure capacity (see Directive 2012/34/EU). However, when setting mark-ups as part of track access charges, the Directive provides for the infrastructure user’s economic situation to be considered (concept of the ability to bear of the market).

In the current charging frameworks of IM, long-distance cross-border passenger services are not fundamentally separated from national long-distance passenger services and it has not shown that TAC are systematically higher for cross-border services. As they are mainly charged per km and cross-border services often result in longer distances travelled, the absolute charge increases with distance though. Based on the same charging principles, long-distance cross-border services are not charged lower than national services either. That is to say that promoting cross-border long-distance passenger rail services seems to have neither been defined as an aim nor a focus by the IM when determining TAC so far.

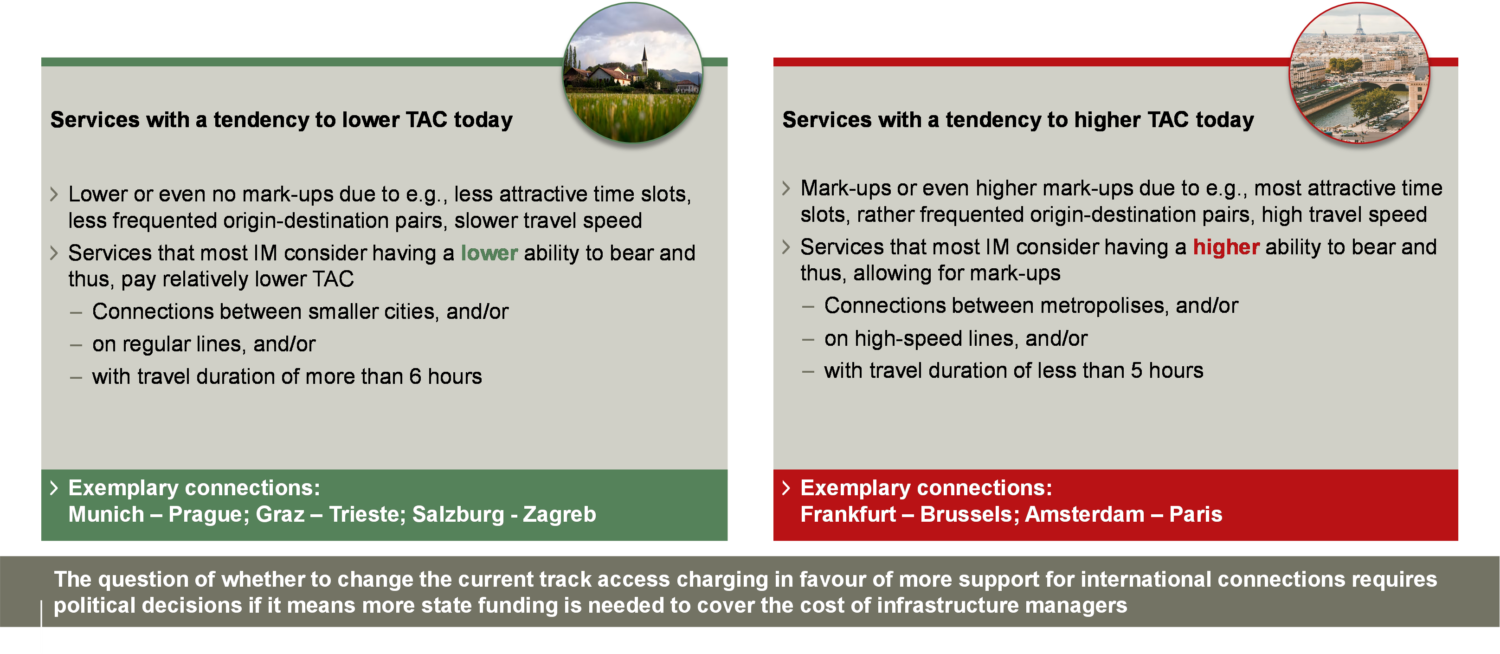

The TAC analysed in the study are explained by various cost and service elements, such as regular or high-speed lines used, weight of rolling stock, and reliability of services. In consequence charges differ between routes and connections. A destination’s attractiveness and population size influence the ability to bear on any route to such destination, regardless of the destination being located domestically or abroad.

Frequently, fast metropolitan connections with a travel duration of less than five hours show common features in terms of cost structures and ability to bear, again regardless of whether they are offered as cross-border or as national services. Costs tend to be higher due to higher speed and more attractive and frequent time slots, which also raise the ability to bear and ultimately the TAC for these services. With higher cost-bearing capacity, connections between international metropolises on high-speed lines tend to be charged higher, applying mark-ups or additional levies. Exemplary cross-border connections are Frankfurt–Brussels and Amsterdam–Paris.

On the other hand, connections between less frequented and smaller cities on regular routes and those with travel durations of more than six hours feature lower costs of service offering and a lower ability to bear – again irrespective of a border crossing. Munich–Prague, Graz–Trieste and Salzburg–Zagreb are exemplary international connections in this category. The question, which of these connections should possibly be promoted, is ultimately a political one.

For railway undertakings (RU), charges for long-distance cross-border passenger services reflect a significant cost component, on top of other additional efforts that result from international services, such as increased administrative and train crew requirements, and specific features for rolling stock. The fact that a reduction of TAC can have a demand-increasing effect on long-distance cross-border services is indicated by the market reactions infrastructure managers have identified in their market analysis and elasticity determinations, expert groups, and modal choice modelling approaches.

The already existing charging policies designed to support certain passenger services form two groups: differentiated TAC and newcomer bonuses.

Differentiated TAC distinguish between international and national connections, or between newly offered connections and connections already established in the timetable. For example, IM offer an international incentive in their charging framework according to which cross-border passenger services pay a reduced TAC by not applying a mark-up, whereas national services pay regular TAC including mark-ups. A new services bonus, on the other hand, offers reduced TAC for all newly offered connections, both international and national. They are applied by some IM for RU that either newly enter the market, or for established RU offering new routes in their portfolio.

Discussions with the IM have shown that intensifying the cooperation with neighbouring networks supports a holistic perspective on long-distance cross-border passenger services, enabling a more unified approach towards such services. In this respect, the experience some IM have made with TAC supporting cross-border services could be evaluated and discussed in more depth between IM, intensifying the existing inter-IM cooperation and alignment with a focus on charging.

The study highlights that, within IM charging frameworks, not all train services contribute equally to cost recovery via TAC, and mark-ups are not necessarily identical for all services. Different abilities to bear come into play here, and cross-subsidisation between different services can be an approach chosen to promote certain long-distance cross-border passenger services. Across all train services, however, total cost must be covered. If this cannot be achieved via charges, higher state funding is required to balance the funding needs of rail infrastructure managers.

A summary of the study results was published by PRIME.